gelatin

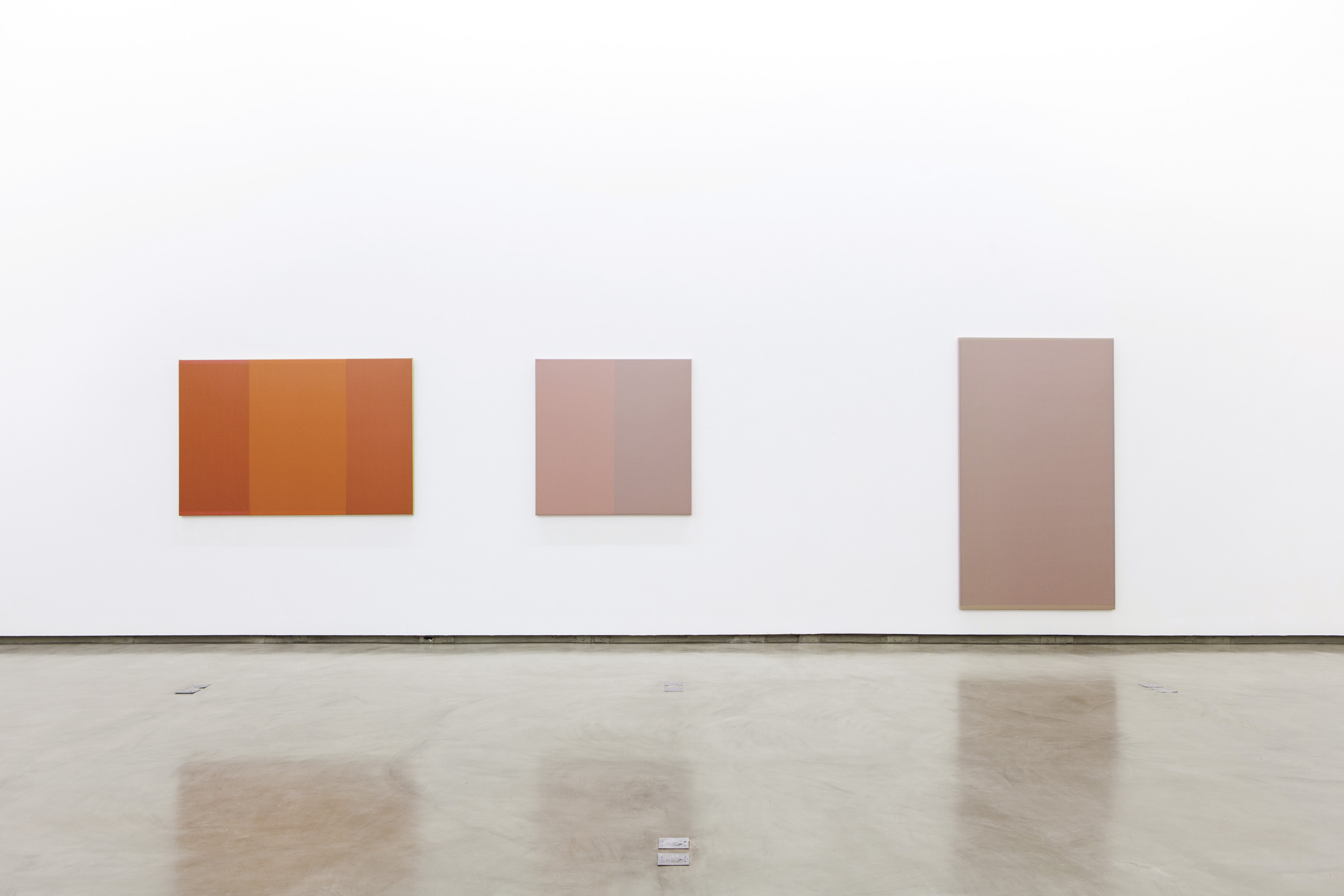

solo show curated by rodrigo naves

anita schwartz galeria de arte, rio de janeiro, brazil, 2013

photos gui gomes

+ about the works

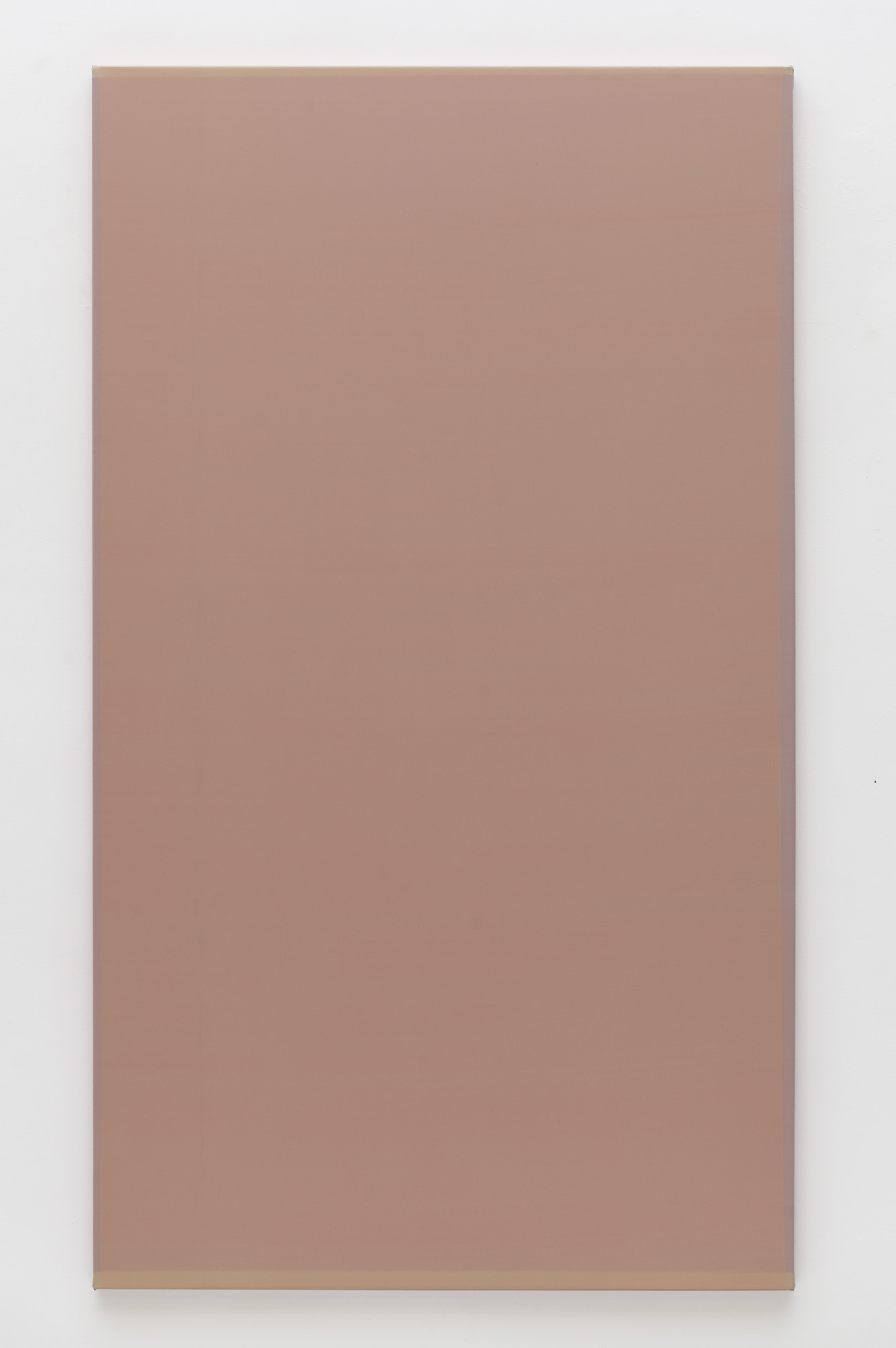

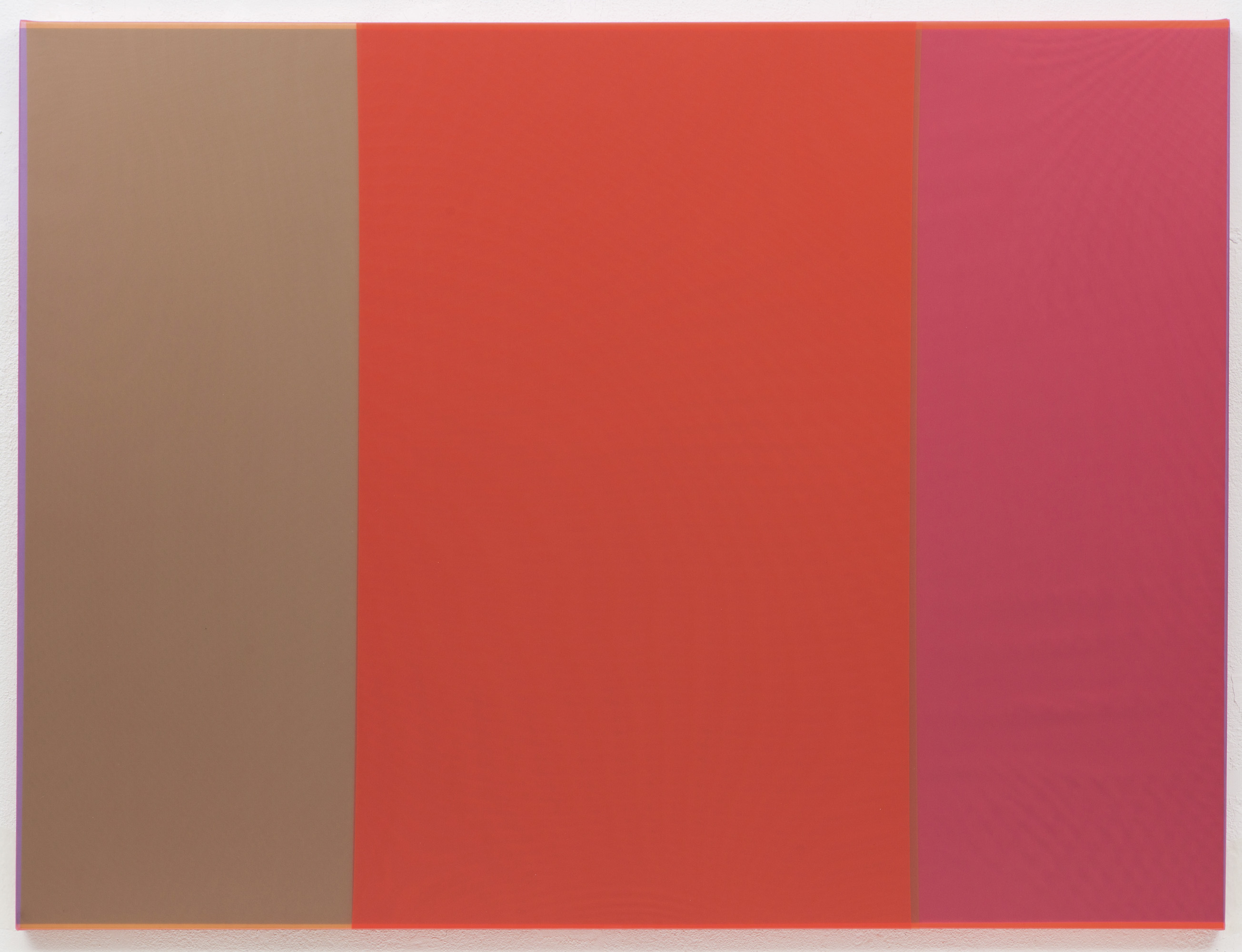

gelatins (from a series of plastic paintings), 2013

curb, 2013

+ catalogue

gelatins and jellyfish for gelatin

rodrigo navesImenos

"... There should be loved even more

a pleasure achieved morbidly and through corruption -

rarely finding the body which feels what it wants -

which morbidly and through corruption, provides

an erotic intensity which health does not know. . . ."

Extract of a letter

written by young Imenos (of patrician descent)

notorious in Syracuse for his dissoluteness

in the dissolute times of Michael the Third.

Constantine P. Kavafy

(translation by Gregory Jusdanis)

The first time that I had the opportunity to write about Estela Sokol’s paintings and sculptures, I used a broad framework to try to think about her work: the ambiguous status of color, as it appears in contemporary artistic production, and its connections with the social experience of our day.[1]

In my opinion, to briefly summarize the previous essay, the artist resorted to materials and colors sourced from Pop (colored acrylic plates and phosphorescent colors) to examine the rigor of geometric shapes long present in constructive art (cubes, for example). On the other hand, the use of artificial and hardly noble materials (like colored PVC bands, for example), of industrial origin or sourced from Pop, achieved very subtle color passages, using a constructive process of overlapping transparencies, which seemed to attain the sophistication of Renaissance veiling.

In this second text, I intend to understand better the meaning of these works, which shift productively between two opposing artistic strands (Constructivism and Pop art), without the slightest hint of that syncretism, typical of postmodern trends, that rarely surpasses a game of quotes and crystalized references. Rather, the artist’s effort is directed towards taking advantage of the possibilities offered by previous artists who worked with what most interests Estela: the experience of color.

In the book L’idée fixe ), by French poet and writer Paul Valéry, during a discussion about what knowledge can be had about men themselves, one of the characters says: "The deepest thing in man is the skin, as long as he knows himself. But what is... truly deep in man, as long as he ignores himself... is the liver... And similar things." I believe that Estela Sokol’s current exhibition touches on issues close to this, even if historical circumstances conspire against her; because, in the contemporary world, recourse to the senses functions more like an appeal, like an eagerness to draw attention, rather than as the intensification of the presence of beings and things.

An unstable surface (the skin) insinuates itself in the very construction of her pictures’ colors – made by superimposing translucent strips of PVC (polyvinyl chloride) – because they show themselves, simultaneously, as autonomous surface and as a result and condition of the other colored strips. In other words, however much we may identify, with greater or lesser clarity, the different areas of color, we also perceive the displacements that lead to the almost sedimentary formation of the other colored fields.

It is almost certain that the character from Valéry’s book is referring to the sensitive, to sensuality – and not to skin in a literal sense. Indeed, it is only when the body becomes something non-objective, when it converts itself into a kind of warm haze, that it effectively stops being the sum of livers, of clearly identifiable organs with precise functions.

Estela's paintings appear to realize, within their own framework, this movement in which the colors still retain some of their light wave nature, without identifying precisely with any particular thing. Enough to think of chromatic shifts associated with temperature changes and skin pressure to understand that her pictures incorporate sensuality, without the slightest trace of figuration. And since the colors obtained by the artist have no shine, they don’t differ, in this respect, from the great majority of other beings of the world, their matte and hazy appearance tending to place us on a plane closer to that of the picture, under the effect of their heat. Paulo Pasta deals with similar issues by other means. With only the help of oil colors and, sometimes, a little wax.

But the refined tonality of many of the artist’s pictures also contributes to this sensual volatilization of the colors. The Italian critic Franco Solmi, in a book about Morandi’s painting, raises possible criticisms of the artist's work that are much more enlightening than the countless compliments lavished on his production.[2] In a decisive moment in his reasoning, Solmi affirms that the Bolognese painter interposes, between viewer and painting, "an impenetrable curtain, a diaphanous diaphragm which allows only the echo of an unrepeatable world. The last Still Life still breathes the corrupted air of that time without present in which Morandi brought to life, for himself and others, and perhaps definitively, the ancient remains of man in the impossible humility of poetry."[3]

This is not the right place to discuss a supposed Platonism of Morandian painting, despite its relevance. However, in my view, this "impenetrable curtain, a diaphanous diaphragm which allows only the echo of an unrepeatable world" can only be understood with respect to Morandi’s extraordinary tonalism. At least since Giovanni Bellini, tonal painting has resorted to shades of a certain color to generate a compositional unity smoother than that of most Florentine painters, other than Leonardo da Vinci. Variations in luminosity of the same color lead the eye to establish a delicate unity amongst them. That is where Franco Solmi’s "diaphanous diaphragm" comes from.

In Estela’s works – qualitative comparisons aside – the solutions move in a different direction. The geometric arrangement of the translucent PVC strips (themselves also regular) seems to offer a challenge to the artist. To wit: how to soften a grid composed of perpendicular bands without transforming the surface itself into a simple patchwork quilt? Undoubtedly, the lowering of the color contrasts – if we compare the current pictures to those shown in the exhibition Pictures and sculptures, in November of 2012 – helped to solve the "problem." But it is this original way of building her colors that is still primarily responsible for the notable response that this young painter is capable of offering to dilemmas central to the art of our time. In Estela’s paintings, those diaphragms might conceal odalisques or nymphs, but we will never uncover the promises kept by these bodies that dissolved in their own ardor.

It remains to be understood why her attention to problems so dear to Morandi (although the artist closest to Estela is Agnes Martin) doesn’t make her merely another representative of the good modern times, with their sad nostalgia. I believe the answer can be found, at least in part, in a text by another important analyst of Morandi's painting, the German Bernhard Growe.[4] In this article, the author concludes his reasoning as follows: “To the exact extent that light becomes corporeal – we seem to perceive the dusty fog of Emilia [the province of which Bologna is the capital] covering the still lifes –, the objects vanish, withdraw, and then become one with each other, and with the clarity that pulls them, without, of course, ever losing the possibility of reemerging. Here there is no l’art pour l'art, but ‘light as metaphor for truth.’ And this truth only knows the world in a state of possibility ('cosidetta realtà') (so-called reality)."[5]

In Morandian tonality, the extreme tonal subtlety is far more than a wistful compliment to the pictorial refinement of the great Italian tradition. The delicacy revealed in his painting is also, simultaneously, the recognition of the risks involved by extreme domestication of the world and the need to maintain it, still, as the site of possible experience.

To achieve this with plastic strips is, nonetheless, a response worthy of the dilemma. In the only sculpture in the exhibition, four marble squares are arranged in a cross shape on the gallery floor. In the center, another square is formed, empty. On the surface of the marble slabs, two parallel grooves have been cut through which run lines of a very light blue, interrupted by the absence of marble in the center of the piece. In short: everything is an interruption in the contemporary game of perception. We perceive something on the verge of appearing, but which interrupts itself halfway there. And it is this emptiness, this fragile place, which the artist wants to render intense, like a white night in Dostoiévski.

november 2013